| Steve Mann | Jason Nolan | Barry Wellman |

| Electrical and Computing Engineering | Knowledge Media Design Institute | Sociology |

| University of Toronto | University of Toronto | University of Toronto |

Correspondence author:

S. Mann, Assistant Mailroom Clerk

mann@eecg.toronto.edu

University of Toronto

10 King's College Road, Mailroom S.F. B540

Tel. (416) 946-3387; Fax: (416) 971-2326

Wearable computing, video surveillance, conceptual art, conceptual artifact, ethnomethodology, action research, ecology, social interfaces, interactional design

The intention of this paper is to resituate the work of Professor Steve Mann, cyborg, inventor, engineer, social critic and artist in the context of sociological discourse. Mann's work challenges much of academia due to its interdisciplinary nature, experimental design, confrontational positioning and performativity. The nature of his design work and inquiry puts him in conflict with many requirements for academic research such as the ethics of informed consent, explicit methodologies and research agendas; requirements that lead most academics to work in labs, controlled spaces, and existing literature. His background in engineering, computers, and performance art as both forms of expression and tools for social inquiry have allowed him to directly engage the social issues surrounding surveillance as part of an emergent research design agenda situated in ethnomethodology and action research [Carr and Kemmis, 1986; Masters, 1995].

What initially began as a form of experimental visual prosthesis (device for modifying the visual perception of reality) evolved into what many regarded as a form of performance art, when certain people objected to Mann's wearing of such visual prosthesis in day-to-day settings. Since the majority of these objections came from establishments where surveillance was used extensively (e.g. gambling organizations that were possibly maffia run) an asymmetry became evident. Early on, it became evident that the more surveillance cameras an organization had, the stronger their objection to a person wearing such visual prosthesis. Thus there seemed an irony ripe for further exploration.

The performative nature of Mann's work, which arose naturally over the past two decades, has meant that he conducts inquiry into the unstable research environment of public (or allegedly "public") spaces such as streets, sidewalks, shopping malls, etc.. Mann's form of 'gorilla inquiry' is action research that takes up his subject through direct engagement, and what could be termed as civil disobedience, or at the very least, disruption of the norms and even unacknowledged acts of oppression by which commercial establishments, corporations, security organizations and their agents (sometimes unwittingly) participate . The authors of this paper, therefore, have collectively chosen to focus attention on the design, conceptualization and performance/inquiry of Mann and his students, rather than trying to do a detailed analysis of the actual data collected using unsuspecting or unwilling participants. It is our goal to replicate or simulate aspects of Mann's work as a follow up project under more traditional research conditions.

Our paper takes up the work of Mann as an example of action research that directly confronts technosocial surveillance using the technologies of oppression as technologies of emancipation, challenging the unstated assumptions of surveillance, ownership of space, and the assumptions of implicit urban interactional contexts. In order to do this we must look at Mann's idea of reflectionism, an interplay of techno-mimesis and tech-nemesis has been applied to the design of a variety of data collection devices based on wearable computers, as part of Mann's eyetap project (http://www.eyetap.org). We then describe how Mann uses his tools to engage in a dialogue with surveillance, to question the social hierarchy surveillance re-enforces. For Mann, issues of social hierarchy and privacy are explored through transgression of technological norms that mirror the technological framework of department stores, gambling casinos, post offices, etc., where surveillance is the primary source of governance and control. The dialogue is initiated by entering these locations and collecting the same kinds of data that are collected through existing surveillance techniques wearing what Mann calls reflectionist devices. His primary goal is to engage in a dialogue with customer service personnel, managers, security workers, etc., while wearing these reflectionist devices, in situations where the devices give rise to a breaking of usually unstated surveillance symmetry rules within these establishments.

A typical example of Mann's method is the collection of video or photographic records within a department store, without permission. Such activity which is expressly prohibited by the customer service personnel under ordinary circumstances, is permitted by the same personnel to continue collecting records if the wearer claims to be unable to stop, for various reasons such as external authority or inability. This has led Mann to suggest that such devices can be used to explore issues of self-empowerment through this type of design.

Reflectionism incorporates a series of concepts that center around the idea of challenging technology-based surveillance as a form of governance. The notion of techno-mimesis and the role of a tech-nemesis as method, location of inquiry, and rationale for inverse-surveillance (sousveillance) situate Mann's work within the Action Research tradition [Steve Mann, "Reflectionism and diffusionism", "Leonardo, http://wearcam.org/leonardo/index.htm", volume = "31", number = "2", pages = "93--102", "1998"] (Carr and Kemmis, 1986). The mimetic act of holding a mirror to the social environment is something that Mann moves beyond written narrative to the actual use of similar surveillance techniques to "watch the watchers", and this ability allows for the potential taking up of the nemetic role of "bringer of social justice" presented as an act of inquiry. Techno-mimesis is a term coined to contain the idea of holding a critical lens (using the tools of surveillance to 'watch the watchers') up to accepted social situations through the use of technology. It partakes of both action research where research inquiry is used to bring about social change, and ethnomethodology which inquires into a social reality that "is an intersubjectively shared and socially constructed phenomenon" [http://www.umsl.edu/~rkeel/200/ethdev2.html] The positioning of Mann's research as antagonistic and directly critical of techno-social surveillance partakes of this desire to enact social change through research inquiry the emergent social phenomenon of technosocial surveillance.

Ethnomethodological and action research inquiry into social phenomena situate Mann's Reflectionism as a position that engages, challenges and inverts the power structure of networked surveillance. The role reversal between the surveilled individual and the act of surveillance, explores the social interactions that are generated by reflectionist observation, and suggest a series of scenarios and questions which Mann hopes to conduct further inquiry; primarily issues of collective- and self-empowerment within the panopticon of social surveillance and the governance of public and semi-public places (Foucault 1977; Ostrom, 1990). Mann's ethnomethodological inquiry leads to the exploration of techniques for repositioning the dialogue on surveillance within a public discourse by empowering the researcher, as a member of the public, to bring the technologies of surveillance to bear on the social hierarchy and those whose profession it is to maintain the hierarchy of surveillance.

Reflectionism challenges the taken for granted notions of ubiquity, location, physical place and cyberspace, by taking them up in the context of transgression, privacy, and technology (Newman, 2000). Contemporary western society has tried to make technology mundane and somewhat invisible through its disappearance into the fabric of our buildings, consumed objects and lives. Through the creation of "pervasive computing", "ubiquitous computing", "smart floors", smart toilets, smart elevators, smart light switches, intelligent environments, intelligence gathering devices, "ubiquitous surveillance", etc., digital technologies are replacing the mechanical technologies of previous generations. And they are becoming equally invisible. But with this re-placement of technologies, and the concomitant data conduits, comes new opportunities for observation, data collection and surveillance. Jeremy Bentham's panopticon defined an observation system in which people could be placed under the possibility of surveillance without knowing whether or not they were actually under surveillance:

the major effect of the Panopticon [was] to induce in the inmate as state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. So to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its actual action; that this architectural apparatus should be a machine for creating and sustaining a power relation independent of the person who exercises it; in short, that the inmates should be caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers. (Foucault,1977, 201)This possibility of surveillance was intended to put the surveilled to be on their best behaviour at all times. Bentham proposed such an architecture for use in prisons, schools, hospitals, and workplaces.(Foucault,1977, 205) Ostrom's notions of self-governance also reflects the traditional importance of observation as a primary force of social cohesion in self-governed communities; that it is the ability to both observe and know what each other is doing that is central to the maintenance of common spaces. (Ostrom, 1990, 59) But what is new can be found by further inquiry into the embeddedness of surveillance technologies, and the unequal access to these technologies, by the general public. The tools of the watcher are now very different than the tools generally available to the watched.

The proliferation of environmental intelligence in the form of cameras and microphones observing public spaces represents new technologies of surveillance and represents a challenge to traditional notions of privacy. The collection of data in public places, with the camera as the dominant form of data input device, is coupled with the integration of surveillance with statistical monitoring and security applications. The passive gathering of intelligence represents a challenge to privacy in public places, that is itself largely unchallenged. Because of these technologies, members of the public are allowing information about themselves, their actions and interactions, to be collected passively, without thought or effort required. (Mann, 2000) This is not an equitable or balanced exchange of information.

Foucault identified in Bentham's panopticon the use of surveillance as a tool for social control, not as a tool for the exchange of information. (Foucault, 1977) He describes the panopticon as part of a hierarchical structure of control which has since become ubiquitous in the modern and post-modern worlds. Bentham describes an institution inhabited by individuals who can not see or interact with each other but know there is a possibility that a guard is watching over them in a central observing tower (the "Panopticon").(Foucault, 1977) Within modern-day establishments video surveillance often takes an analogous form. Video cameras can be visible, or conspicuously concealed, under mysterious hemispherical domes, and the public does not know which domes have cameras, or how many cameras are in each dome, or which way they are pointing. Even if feedback is provided via a visible television displaying the output of hidden cameras, there is still uncertainty as to where and how many cameras there are. The function of domes themselves can not easily be perceived, as they do not take the form or shape of what one traditionally associates with a camera. As a result, the domes suggest surveillance, but otherwise remain unclear. When asked what the domes are, various customer service personnel provided various answers, ranging from statements that the domes are light fixtures or temperature sensors, to claiming to be ignorant of what they are. For example, a Sears customer service worker described the dark hemispherical domes as temperature sensors, and, when asked what the temperature sensors were for, the Sears representative explained they were for adjusting the temperature of both the heating and air conditioning systems. See for example, http://wearcam.org/shootingback/sears.mpg where the Sears representative provides such an explanation.

The Panopticon is designed such that the knowledge that there may be surveillance is sufficient to induce obedience to authority (Foucault, 1977). One way to challenge and problematize both the obedience and surveillance is to take the same panoptic elements and re-situate them on the individual to watch those in authority. We coin this inverse-Panopticon as being "sousveillance" from the French for "sous" (below) and "veiller" (to watch). (Mirriam-Webster, 2002). Examples of sousveillance include: customers photographing shopkeepers; taxi cab passengers photographing cab drivers; citizens photographing police officers; and civilians photographing government officials. In many cases, this violates prohibitions on non-employees using recording devices. Following the methodology of Garfinkel who gained insight into unspoken social rules by being deliberately deficient in social co-operation and refusing to "play the game", Mann's mirroring of establishment surveillance and thus breaking known policies, forces an examination of the interactional outcomes and behavioural effects on authority figures (Garfinkel, 1967; Mann, 2000; Mann 2001). This work is unique in that Mann is not designing for a particular user, but he is designing for a particular situation: the violation of rules. Due to the need for an incidentalist and bureaucratizable environment that travels with the wearer, it makes sense to situate the device on the body of the surveilled (customer, taxicab passenger, consumer, etc.) in the form of wearable computing devices.

Researchers such as Spears and Lea (1994) have discussed the ability of computer-mediated communication to equalize or reinforce power relations. And in certain social contexts, it has been suggested that Foucault's metaphor can be extended to computer-mediated communication as a form of increased social control by reinforcing established bureaucratic relations. In fact, Foucault states just this: "Panoptism was a technological invention in the order of power, comparable with the steam engine." (Foucault, 1980b, 71) In contrast,by reducing observeability, as well as cues to status and power, individuals are less likely to be influenced by them resulting divergence from group conformity and obedience to powerful others. We have not yet identified any research into face-to-face computer-mediated communication (communication involving computers where individuals are co-located in a single physical space) designed purposely to challenge or problematize the power relationship initiated by observation.

Stanley Milgram's (1977) work on the collection of data (photography) takes up similar issues. He describes how people would go out of their way to assist photography. Fully blocking a New York City sidewalk, he found that thirty-seven percent of people would not violate the line of sight between camera and subject. Repeating the experiment with playing ball and no camera, ninety-one percent of people walked through the game. Unlike playing ball, the act of photographing something is seen as an acceptable enclosure of public space. Conversely, photography is also seen as the greatest infringement on privacy, as shown by attempts to suppress photography in situations where people go out of their way to disrupt the camera (e.g. putting their hand over the lens, etc.).

Solutions offered to privacy concerns have mainly dealt with technology enhancements, such as developing rules and protocols to negotiate privacy between personal agents and the environment [Rhodes et al., 1999]. Personal empowerment in wearable computing has also focused on enhancement via software features to augment one's knowledge base. However, access to more information does not imply greater self-power as this information could be controlled or exchanged via an external agent. Personal empowerment, though, can also be viewed in a social context on its human-human interaction effects. It is this social form of self-empowerment which Mann seeks to examine through the design of the devices to force a dialogue between the customer and customer service personnel regarding surveillance policies in commercial establishments.

Instead of designing devices and interfaces for the user as consumer of a product, Mann designs for situations where the focus is the dialogue that develops between the wearer of the various device(s) and individual in public and commercial venues. Ethnomethodological inquiry embraces the level of uncertainty that surrounds these dialogues. No one is ever sure of the outcome of the interaction between device, wearer and conversant. Mann work with the understanding that design factors can influence sociological factors of interaction [Dryer, et al., 1999]. For example, it has been suggested that people who use more familiar mobile devices (such as laptop computers and personal digital assistants) are perceived to be more socially desirable than those with less familiar devices [Dryer, et al., 1999]. The wearing of technology can be seen as either acceptably empowering or unacceptably threatening, depending on the type of technology and location. The opportunity for engaging in sociological discourse about the role of technology and surveillance in our society changes based on numerous factors as well. A central goal, however, is to understand how an individual who is wearing sousveillance devices is perceived, as well as how attitudes toward surveillance and sousveillance are reinforced or challenged.

Mann's Reflectionism (techno-mimesis/techno-nemesis) centres on the use of the wearable technology as a persuasive tool to challenge attitudes and behaviours [Fogg, 1997]. In Mann's case, the wish to record the behaviour of customer service personnel (and other unknowing and unwilling participants in his performance/activism/research) when interacting with the wearer of a sousveillance (e.g. recording) devices in various situations. Mann's reflectionist project of sousveillance sees the dominant issue of interest to be the unchallenged nature of individuals being under surveillance by establishments. Also, at the individual level, Mann's program of inquiry entails the engagement of the frontline agents of commercial establishments in the form of customer service personnel, floor managers and security personnel in an effort to co-problematize their work environment.

Reflectionism is related to the Situationist movement in art, in particular the aspect of what Situationists refer to as "detournement" [Rogers, 1993; Ward, 1985]. This tactic appropriates tools of an "oppressor" and immediately resituates them in, hopefully, a disorienting and disturbing manner. Surveillence is inverted through mimesis into a form of confrontational action research that partakes of the nemesis, a divine justice, or "payment... duly made" in having the tables turned, and the power structure inverted [Graves, 1955, 126-7]. Reflectionism extends the concept of detournement by additionally using the tools against the oppressor, holding a mirror up to the establishment, and creating a symmetrical hierarchy and self bureaucratization of the wearer [Mann 1998]. The mimetic symmetry that is created is meant to stimulate self-reflection problematizing the situation for all parties involved.

A nšive interpretation of Reflectionism might leave one to think it is nothing more than bothering low-level customer service personnel and engaging only the lowest level personnel who are merely symptomatic of a systematic problem, not the progenitors. However, with Reflectionism, Mann does very successfully and directly challenge "the system" and not just the low level individuals who work for commercial concerns:

In Mann's case, the mimetic/nemetic persuasion comes as a result of computer-mediated communication. The difference between his work and the captology framework [Fogg, 1997] is that he is not persuading users of his tools of inquiry (e.g. wearers of the devices) directly. Instead, he is attempting to persuade people who interact with wearers of his devices within the context of their normal daily activity (e.g. when users of his devices shop at department stores, or carry out various daily routines, etc). The dimension of behaviour under examination is that of trying to open a dialogue with workers, with the goal of helping them to see that they are part of an oppressive social hierarchy.

If customers complain about the establishment's surveillance system, such as the mysterious ceiling domes, Mann's research suggests that the customer service personnel either claim not to know what is in the domes or the customer service personnel absolve themselves of responsibility by redirecting him to speak with "the manager" [Mann, 2001]. The manager can be bound by or can pretend to be bound by policies from a CEO, who is bound by a board of directors, and so on. The bureaucracy creates a credible and unquestionable authority allowing customer service personnel to pretend to (or actually) have no control over their actions. Customer service personnel therefore externalize and absolve themselves of responsibility for a social order they complicitly help to maintain. Using reflectionist design to mirror establishments' surveillance and bureaucracy, we have created a situation of inverse-Panopticon surveillance (what we call "sousveillance").

Mann has conducted experiments over a 22 year time period in various countries around the world, under a wide variety of circumstances. Because multiple observers (film crews, investigative television crews, etc.) were often present inconspicuously, to document the event, it can be maintained that the reliability of noting important details and description of at least some of the observations and circumstances was high. The observations further supplemented the experiences of many years of usage with similar devices, in less formal acts of inquiry.

Mann inverts Stanley Milgram's camera experiments where people facilitate the taking of photographs [Milgram, 1977] by examining the degree to which customer service personnel will try to suppress photography in locations where it is forbidden. Unlike many establishments' use of surveillance, Mann often deliberately makes it clear to customer service personnel that their image is being taken. This is accomplished by providing appropriate image feedback on either a wearable flat-panel screen or a wearable data projector. The pictures were taken with either an EyeTap device, or a covert pinhole camera, a highly obvious camera with flash, or a camera conspicuously concealed (blatantly covert) under a wearable version of the ubiquitously familiar ceiling dome. Mann suggests that the probability of interaction decreases with a decrease in device overtness [Mann, 2001]. By having a salient display, debate is instantaneously provoked without the need for any comments from the wearer of the devices who are initially secondary in the interaction.

The intended purpose of these kinds of wearable computing devices is to provoke a response from individuals the researchers confront during their interaction. Because the designs of the devices draw on reflectionism and the Situationist art movement, the observations are often said to correspond to a performance. During these performances a series of observations are made that vary the device type and the externality continuum [Mann 2001].

Performance One: Wearable computer with power battery operated wearable data projection systemThis performance involves a wearable computer with a wearable high power mercury vapour arc lamp, data projector, etc., all running from a wearable power pack, as shown below:

The projector was aimed at the ground, with the image projected upside-down (from the wearer's viewpoint) so that it created a projection space visible rightside-up to people facing the wearer.

In the first performance, while setting up and getting ready (e.g. with the devices inactive) Mann found that people spent less time attending to the wearer of the apparatus and the device itself.

Interestingly, when the display was not on, and investigators were stationary chatting and mulling on the street passers-by come up to the computer wearer and immediately ask unrelated questions, such as asking for directions. One wonders why the passer-by selected the computer wearer when deciding who to ask for directions. Perhaps it was the novelty of the device or a perception that the computer wearer has more access to local knowledge, etc., that prompts the individual to select the wearer. Once the set-up is complete, the display stimulus consists of the dynamic video of passers-by combined with the text "www.existech.com" which are projected on the ground. At this stage, the wearer of the device walks in the crowded downtown streets of a major metropolitan city on busy evenings. This performance is designed to gauge the reactions of ordinary citizens towards the device itself, unaccompanied by any explicit confrontations. The nature of the displayed material greatly affects attitudes and perceptions of the device itself. For example, when the text displayed on the ground contained a ".com" URL, many people associated the device with a corporation, asking questions such as "what are you selling today?" Additionally, this appears to help legitimize the device, positioning it as a marketing tool. Although the device has a strange appearance, the fact that people interpreted it as advertising, somehow mitigates that novelty.

Experience gained from this type of performance suggests that it would be revealing to further probe the level tolerance and acceptability towards the device and wearer, and if it is related to whether the device is sanctioned by a corporation or some other credible external authority. Though of course, technology is often itself seen as a form of authority.

Performance Two: Projected data with input from hidden camera

In this act of observation, a concealed infrared night vision camera is used to capture live video of passers-by, and then display the live video for those present to see. The camera itself was well hidden, but the effect of the camera (the live video) was made very obvious by the extremely intense beam of the data projector and the novel arrangement of the projection. The update rate was approx. 10 frames per second.

Various text, graphics, and other subject matter displayed by the high power wearable data projector evokes a variety of different kinds of responses. Among the most visceral of responses are when people see their own picture incorporated into the display in some way. For example, when images are captured of people, and then turned into a computer-generated advertisement, these people paid much more attention to the advertisement in which they themselves are the subject, than they did to other similar video material. People seem captivated by computer generated content of which they themselves are the subjects.

In the simplest form,

the video output of the hidden camera is displayed directly to the

data projector. This

definitely captures the attention of the audience. One of the most

common reactions is that people would try to find the camera, and

become quite captivated (disturbed, amused, or obsessed)

by the apparent absence

of a camera but the obvious presence of themselves as live video

projected onto the ground. In other forms, text, graphics,

and other content containing images

from the hidden camera is generated on-the-fly and rendered to the

data projector for the audience. The update rate is approximately 10

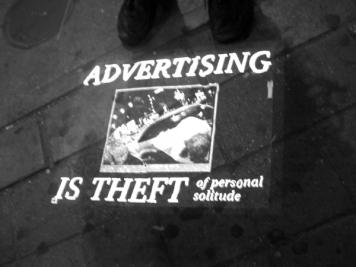

frames per second of live video. Provocative text messages such as

"ADVERTISING IS THEFT of solitude" are mixed with video from

the concealed night vision camera system.

The wearable apparatus contains a 1 GHz P3 CPU, rendering engine, high power mercury vapour arc lamp data projector, within a black flame-retardant Nomex(TM) uniform custom tailored to fit the wearer. Here a person can see his own image together with other computer generated material. (b) Close up view showing the output of the high intensity data projection system. The apparatus has been worn into many establishments such as department stores, shopping malls, etc., where photography is strictly prohibited. Mann states that customer service personnel often chose to ignore the rather obvious fact that a camera is present, because there is no object present that corresponds to what a consumer thinks a camera should look like.

This system gave rise to a roving interactive performance space, wherein the roles of artist versus spectator, as well as architecture versus occupant were challenged, as shown in the following:

(a) On the street, people would bring their children over to play in the wearable interactive video environment and performance space. (b) Large crowds gathered to see the interactive environment. (c) Even adults enjoyed playing in the interactive space.

Especially interesting was the favorable reaction of the public to this kind of gorilla inquiry. Challenging the notion of surveillance, along with the role reversal (surveillance versus sousveillance), gave rise also to a reversal of performer versus audience. In a sense the ordinary people walking down the street became street performers and artists on the wearable "stage" that moved over to them as the wearer walked toward them. The "stage" itself, which is ordinarily thought of as a piece of architecture, became a piece of clothing.

These relationships became even more interesting when wearing the apparatus into spaces such as shopping malls, that are only semi-public rather than fully public:

Performance Three, Making the camera very obvious

In this performance, two cameras used with the high intensity wearable projection computer system, including: the concealed infrared night vision camera of Performance Two, and an additional ordinary hand held camera mounted to headgear. The purpose of using the additional camera was to make the act of taking a picture very obvious. Firstly, the additional camera chosen (a Kodak DC 260) looks very much like a camera, so that its function is very obvious. Also, unlike the infrared night vision camera it has a loud simulated click sound, that calls attention to itself whenever it takes a picture. Moreover, it has a built in electronic flash, so that even if customer service personnel are facing in the opposite direction, they are quickly alerted to the fact that a picture has been taken. The device corresponds to consumer conceptions of what a camera should look like. When they turn to see what caused the flash, they can see their picture projected on the ground. To make the image capture more obvious, both pictures (still freeze-frame, as well as live video from the infrared imaging system) are displayed side-by side. The flash serves as a very effective annunciator, to indicate clearly that a picture is being taken every 19 seconds (the update rate of the color still camera). The text "CAMERAS REDUCE CRIME..." is used in the projection, together with the still and video displays. The observations begin in a series of shops, restaurants, malls, department stores, and the like, and ends on a street as with past performances. In many establishments, objections are raised to the taking of pictures for reasons that tend to centre around establishment policy.

If the wearer does not appear to be under control of the apparatus, that customer service personnel often permit the wearer to continue to remain in the shop in some iterations of the experiment. Measures are taken to ensure that the wearer appears to have no control over the apparatus:

Mann notes found that shopkeepers, customer service personnel, and other officials would often permit or accept the fact that the wearer is taking pictures in their establishments, when the wearer could attribute these acts to external (e.g. non-voluntary) circumstances or control, at one of the various steps along the externality continuum describe earlier.

As well, the wearer can claim to be subject to various obligations to not remove the device:

Other variations on similar themes, include deliberate prior adjustment of the camera so that it would malfunction and get stuck in the "on" position. When such malfunction is explained to the customer service personnel, they often accept the photography in their establishments.

It was found that the greater the appearance of personal control, the less acceptable the act of image gathering. For example, the level of tolerance and acceptability for taking pictures varies according to the degree of the externality continuum. At the extreme, if the wearer explains the fact that he is not in control of the device and does not know when it takes a picture, then the majority of customer service personnel do not object to a wearable data-collection computer system. And while initial objections to photography are often quickly made, after diffusing the control and responsibility of the device to an external authority, the customer service personnel often make no further comments.

In other situations, if the wearer appeared to be "just following orders" mirroring the usual response patterns Mann observed in customer service personnel, the act of taking pictures was tolerated. For example, a wearable camera made very obvious by flashlamp and a loud click for each picture, as well as by display of image content, was found to produce an extreme negative reaction. But the negative reaction could be countered by using a headset with microphone, and talking to a remote "boss" and explaining loudly, "They seem to be objecting to having their pictures taken...."

Compliance, or apparent compliance, to a credible external authority, seems to reduce objections made by customer service personnel. Ideally, to be most effective, the wearer needs to be "oppressed" in the same way that the customer service worker is "oppressed". Thus, for example, the wearer of the eyeglasses is required, by an external manager, to wear the eyeglasses, while running errands on company time. Thus if the wearer of the computerized eyeglasses is simply wearing a uniform while purchasing some items for his company's business, and the eyeglasses are part of the uniform, there is greatly increased acceptance of the wearer's requirement to wear the uniform. In some versions of the eyeglasses, a "comfort band" was designed to go around the back of the wearer's head so that the wearer could not remove the glasses.

In this way, the wearer and the department store customer service worker can feel sorry for each other's state of "oppression" while their respective managers require them to photograph each other. Meanwhile, while they engage in what would normally be a hostile act of photographing each other, they can be quite collegially human to one another, and discuss the weather, the baseball game that was on TV last night, or how terrible their respective managers are treating them by forcing them to photograph each other.

(a) Projected text: "Cameras reduce crime; for your protection your image shall be recorded and transmitted to the EXISTech.com image recognition facility. (b) Confrontation with top officials at an upscale jewelry store. (c) A favorable reaction was obtained from department store security staff who thought the device was a good invention.

Performance Four: Conspicuously concealed cameras with wearable flat panel displays

Whereas performance three targeted primarily at upscale jewellery stores, gambling casinos, and other establishments being similar in nature to those in which the investigators had been required to leave, the goal of this set of performances is to create an ambiguous situation in which data-gathering wearable computer systems are conspicuously concealed. For example, "blatantly covert" domes are used. (See Fig. domewear.)

This figure shows a line of products, along with a corporate brochure that was created to present the artifacts in the context of purchased goods. As a result, a department store security guard objecting to the wearing of such apparatus would also, by implication, be objecting to a legitimate product of the legitimate consumerist society that his or her store was trying to uphold. Some performances involves re-situating surveillance domes onto wearable computers. Some of the experimental apparatus also incorporates various large flat panel data display screens, worn on the body, displaying video from a concealed camera, or even from a previous trip to the same shop (e.g. "no camera", so that when told that photography was prohibited, the wearer could indicate that no camera was present and that he was merely playing video recorded previously from the same shop).

In one situation, the investigators offer to cover up the data display with a piece of paper so that it would no longer bother the customer service personnel. (See Fig. paperscreen.)

These images relate to a particular experience where individuals (presumably undercover security guards) object to the mere display of images captured within their retail establishment. The wearable computer with wearable 640x480 video display device is found to be most disturbing when it plays images of merchandise similar to that which come from a camera in this establishment, regardless of whether or not a camera was actually present. When persons claiming to be staff of the establishment objected to the video displays, the investigators offered to cover up the displays with sheets of paper. This offer to cover up the wearable display devices, so that the images would no longer be visible, are presented as a means of isolating the issues of privacy (the right to be free of the effects of measuring instruments such as cameras) from the issues of solitude (the right to be free of the effects of output devices such as video displays).

This situation created a distinction between the often conflated issues of privacy (as is violated by input devices such as cameras) versus solitude (which is violated by output devices such as video displays). The wearable computers with domes are found to create a very interesting dialog, because the size of the dome could be varied, e.g. a number of wearers having progressively larger and larger domes would enter an establishment until a complaint was raised. Answers would need to be provided to the customer service personnel. In some cases, the investigators played back video recordings of the same customer service personnel, or of other customer service personnel in other shops. The video recordings had been generated by entering the shops with hidden cameras and asking the customer service personnel what their domes on the ceilings of their shops were. For example, the investigators had a recording of department store customer service personnel telling that the domes on their ceiling were temperature sensors. A record store owner had told the investigators that their dark ceiling domes were light fixtures. By playing back these recordings with flat panel displays, for the customer service personnel to see, a true form of reversalism took place. It was found that the same kind of surveillance domes used by establishments could be reflected in wearable computing. These hemispheres of wine-dark opacity which may or may not contain surveillance cameras, and are so commonly found on the ceilings of many shopping establishments and gambling casinos, now give way to a true reflectionist model. The fact that the domes may or may not contain cameras creates an important design element for the wearer, because it is possible to arrange the situation such that the wearer does not know whether or not the apparatus contains a camera. Thus when questioned about the wearable domes, the investigators could reply with uncertainty.

Another element of the performance is a mockery of visibility and transparency. In one performance, a back-worn wearable flat panel display was arranged to show a view from a front-worn camera. When asked what this apparatus is, the wearer says that it is an "invisibility suit". This notion is nonsense, in the sense that the device certainly does not give invisibility (in fact it attracts all the more attention). However, it was found that by presenting the camera as art (e.g. as in Magritte's 1936 painting of a painting showing reality, as described in http://wearcam.org/easel.htm), unusual actions are accepted. Presenting the camera as part of a form of theatre, in the context of a humourously nonsensical invisibility suit performance, somehow legitimizes it, as an externality.

A similar result was found when the investigators described the domes as "lucky charms to chase away evil spirits". Such a nonsensical attribution to a clearly external force or notion or nonsense, was found to greatly increase the acceptability of wearing computers in establishments where cameras are normally strictly forbidden.

Conspicuously displayed cameras are worn in establishments where cameras are prohibited. A large 1024x768 flat panel display has been incorporated into one of the wearable computer systems. To maximize screen size on the body, the screen was mounted sideways. The second image shows Sousveillance under surveillance: standing under one of the department store's ceiling domes. The third image shows a backworn display shows output from a frontworn camera, so that people can see right through the wearer. The wearer's back has a window, showing what is in front of the wearer. And when asked what the device is, the wearer responds with a nonsensical answer, namely that the apparatus is an invisibility suit to provide privacy and protection from surveillance cameras. Such a silly answer externalizes the locus of control of the wearable camera, first such a crazy idea as an invisibility suit makes it hard for the customer service worker to reason with the wearer. Second, this is obviously performance art, fashion, and theatre of the absurd, the technology being a necessary part of the performance piece. Third, the wearer can argue that the motivation for wearing the camera is to protect the wearer from being seen by the department store's camera. The wearer can even claim that his manager requires him to wear the invisibility suit. The customer service worker's objection to the wearer's manager's sousveillance camera is transformed into an objection to the customer service worker's manager's surveillance camera.

Participant as Subject

The notion of the subject in photography refers to the primary content of the captured image. It also includes the idea of being subject to authority, or to being captured; subjectus"one under authority" . Whether being subject of state authority in a democracy, or the subject of a dictator, we are often subjected to the scrutiny of the carcereal state or surveillance society.[REF] When an individual or researcher enters an establishments we become sometimes unwilling and sometimes unknowing subjects of surveillance. Mann's acts of sousveillance redirects an establishment's mechanisms and technologies surveillance back on the establishment; the gaze is inverted. Often the subject of this inverted gaze is a customer service worker, and Mann's curiosity with regards to the customer service worker's behaviour is located in an interest in responsibility for one's own actions, and he continually challenges the notion of an individual who participates in an oppressive act as merely doing one's job. The attempt is to situate the a dialogue on surveillance in the larger context of democratic social responsibility.

Mann's challenge to authority is both technology and social. On one hand, his program of inquiry is that of the nemesis, using the power of authority to challenge and overcome authority, or figures of authority. There is an explicit in your face attitude towards his inversion of surveillance techniques that draws from the women's rights movement, aspects of the civil rights movement, and radical environmentalism. And it is not possible to discount the work as mere performance, or as an aesthetic exercise. Each performance is directed towards institutionalized surveillance tools that are as much part of militaristic and authoritarian regimes as they are for transglobal corporations. And Mann's refusal to absolve the 'customer service worker', as he puts it, from culpability, is a refusal to allow the autonomous individual to escape from personal responsibility for one's actions.

As with Milgram's experiments, which revealed how individual's responses changed when they felt they were being observed, Mann challenges the complacency of the observers. Milgram showed that the presence of a camera induced people to give larger charitable donations, (Milgram, 1977) believing that the camera alters the level of anonymity and responsibility. By having a permanent record of the situation beyond the transaction, social control is enhanced. Ingham also examined how privacy is a psychological requirement, (Ingham, 1978) and that in personal relationships, people have control over the degree of anonymity they posses in the relationships, by, for instance, choosing what personal information to reveal to another person based upon their relationship. Surveillance cameras threaten this autonomy. And shrouding cameras behind a bureaucracy results in somewhat grudging acceptance of their existence in order to participate in public activities (shopping, accessing government services, traveling, etc.).

Ingham further discusses that the asymmetrical nature of surveillance is a characteristic of a power relationship, saying that "for a policeman or customs officer to search through one's belongings or pockets is a reflection of the power they possess in that one cannot search through theirs", (Ingam, 1978) a sentiment firmly located in the "panopticon", in the asymmetric photography/video policies of the examined establishments themselves.

Sousveillance breaks down the power relationship of surveillance. The presence of sousveillance has been shown to be accepted when justified by the same justification for surveillance, namely that of an external locus of control. By designing wearable computers within this reflectionist framework, wearable computers become tools for self-empowerment.

Mann's purpose, however, is not to advocate the usage of overt and large devices, such as those used here, in day-to-day activities. Rather, to illustrate the use of reflectionism and captology as tools of inquiry and praxis.

The social-aspect of self-empowerment suggests that sousveillance is an act of liberation, of staking our public territory, a levelling of the surveillance playing field. But it is challenged by the thought that the total surveillance that sousveillance affords is an ultimate act of acquiescence on the part of the individual. Universal surveillance/sousveillance would only serve the ends of the existing dominant power structure. It would not prevent terrorism, by individuals, organizations or institutions. It would not serve much purpose in holding officials accountable for actions. Sousveillance is a conceptual model of reflective awareness that seeks to heighten awareness of social interactions and factors of contemporary life. It is a model, with its root in previous emanscaptory movements, with the goal of social engagement and dialogue.

Mann's demonstrations of how reflectionism and captology can be used in device design and to generate "sousveillance", and his using of devices in a deliberately obfuscatory manner not only shines a bright light on the issue of surveillance, but explores mechanisms to challenge social norms, as a way of opening dialogues. The issue is not about how much surveillance and sousveillance is present in a situation, but generating an awareness of the disempowering nature of surveillance, its overwhelming presence in western societies, and the complacency of all participants towards this presence.

Authors would like to acknowledge the many people who helped out or were involved in various ways: James Fung, Corey Manders, Betty Lo, Angela Garabet, Adwait Kulkarni, Samir, Sharon, Tomas Hirmer, Chris Aimone, and Angie, as well as others who helped contribute to the project: CITO, NSERC, Kodak, Xilinx, Altera, etc..

Bell, D. and B. M. Kennedy, Eds. (2000). The Cybercultures Reader. London, Routledge.

Carr, W. and S. Kemmis (1986). Becoming Critical: Education, Knowledge and Action Research. London, The Falmer Press.

Coyne, R. (1999). Technoromanticism: digital narrative, holism, and the romance of the real. Cambridge Mass., MIT Press.

Dryer, D.C., Eisbach, C., Ark, W.S. "At what cost pervasive? A social computing view of mobile systems." IBM Systems Journal 38, 4 (1999), 652-676\\

Fogg, BJ. Captology: "The Study of Computers as Persuasive Technologies", in Extended Abstracts of CHI '97 (Atlanta GA, March 1997), ACM Press, 129.\\

Fogg, BJ. "Persuasive Computers - Perspectives and Research Directions", in Proceedings of CHI '98 (Los Angeles CA, April 1998), ACM Press, 225-232\\

Foucault, M. (Sheridan, A. trans) Discipline and Punish Vintage Press, New York, 1977.\\

Foucault, M. (1980a). "Prison Talk." Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. C. Gordon. New York, Pantheon: 37-54.

Foucault, M. (1980b). "Question of Geography." Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. C. Gordon. New York, Pantheon: 61-77.

Garfinkel, H. Studies in Ethnomethodology . Polity Press, Cambridge UK, 1967.\\

Gaver, W. and Dunne, A. Projected Realities - Conceptual Design for Cultural Effect, in Proceedings of CHI '99 (Pittsburgh PA, May 1999), ACM Press, 600-607.\\

Graves, Robert. (1955) "Nemesis". The Greek Myths: 1. Harmonsworth: Penguin.

Ingham, R. Privacy and Psychology, \textit{Privacy}, John Wiley \& Sons, 1978, 35-57\\

Masters, J. (1995) 'The History of Action Research' in I. Hughes (ed) Action Research Electronic Reader, The University of Sydney, on-line† http://www.behs.cchs.usyd.edu.au/arow/Reader/rmasters.htm (download date 00.00.0000)†

Mann, S. Can Humans Being customer service personel make customer service personel be Human? - Exploring the Fundamental Difference between UbiComp and WearComp. Informationstechnik and Technische Informatik 42, 2 (2001), 97-106.\\

Mann, S. Computer Architectures for Protection of Personal Informatic Property: Putting Pirates, Pigs, and Rapists in Perspective. First Monday 5,7 (July 2000), http://www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue5\_7/mann/\\

Mann, S. "Reflectionism" and "Diffusionism": New Tactics for Deconstructing the Video Surveillance Superhighway. Leonardo 31, 2 (1998), 93-102.\\

Milgram, S. The Individual in a Social World. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., London UK, 1977.\\

Newman, Judith M. (2000, January). Action research: A brief overview [14 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 1(1). Available at: http://qualitative-research.net/fqs [Year, Month, Day].

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Ostwald, M. (2000). "Virtual Urban Futures". The Cybercultures Reader. D. Bell and B. M. Kennedy. London, Routledge.

Pentland, A. and Choudhury, T. Face Recognition for Smart Environments Computer 33, 2 (2000), 50-55 \\

Rhodes, Bradley J., Nelson, Minar and Weaver, Josh. Wearable Computing Meets Ubiquitous Computing: Reaping the best of both worlds, in Proceedings of The Third International Symposium on Wearable Computers (San Francisco CA, October 1999), 141-149.\\

Rogers, Ted W. in Gupta, Sunil (ed) Disrupted Borders: An Intervention in Definitions of Boundaries, Rivers Oram Press, London UK, 1993\\

Spears, R. and Lea, M. Panacea or Panopticon? The Hidden Power in Computer- Mediated Communication Communication Research 21,4 (1994), 427-459\\

Schumacher , E. F. (1973). Small is Beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. London, Blond and Briggs.

Trifonas, P. P. (2001). Barthes and the Empire of Signs. Cambridge, Icon.

Ward, T. The Situationists Reconsidered, in Kahn, D. and Neumaier, D. (eds.), Cultures in Contention, The Real Comet Press, Seattle WA, 1985. \\

Weber, M. (1993). Basic Concepts in Sociology. New York, Citadel Press.